If you have followed this blog at all, you will have learned by now how I emphasize that photography is all about light...not the quantity of light, but the quality of light. Quality light comes from many sources and is influenced by time, place, season, subject, angles, color, and intensity. More importantly, quality light depends on you the photographer to seek it out and recognize it.

Recognizing quality light takes a bit of practice, but there are a few things you can count on to almost always find it. One of the easiest is to 'shoot the transitions'. Transitions are those times during the course of any given day when the light begins to change from one form to another...high to low, low to high, cool to warm, warm to cool, direct to filtered...and so on. let me give you some examples.

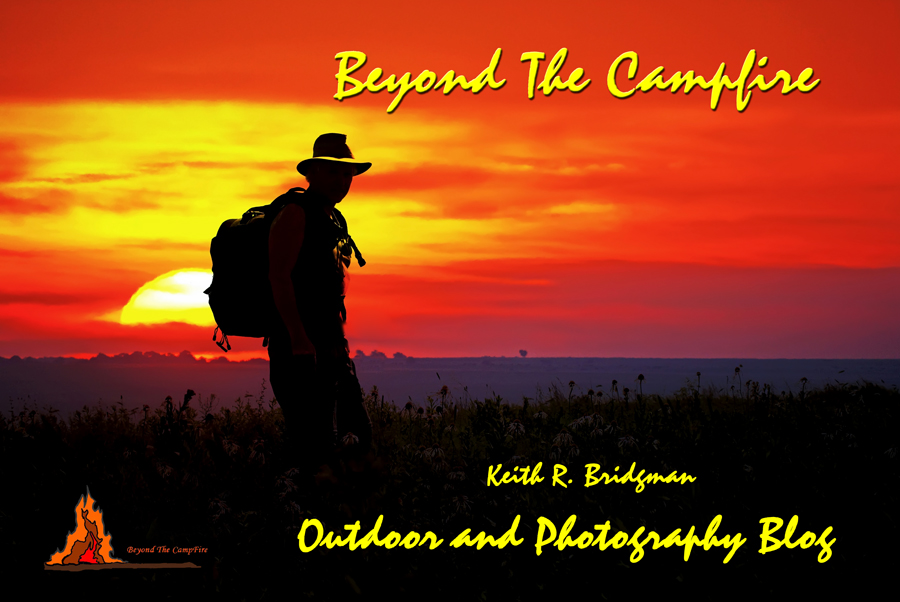

The most obvious transition occurs at sundown when the bright and flat light of the day begins to drift toward a warmer, sometimes bolder, sometime more subtle, colors when the angle of the sun has to filter through a thicker part of the atmosphere. Sunsets are also somewhat of a cliche...everyone photographs them and there isn't a sunset that has ever happened that hasn't been photographed somewhere...sometime. I still find myself drawn to them, but I often instead photograph the effects of the sunset light as opposed to the direct sunset itself. The soft warm nature of the sunset light casts a warm glow on everything it touches. Sunrise on the other hand can offer an even more variety of transitional lighting conditions. The predawn sky can vary from soft pastels to bold reds and yellows. The trick is to use these color transitions within the context of time and place.

Although sunsets and sunrises offer the most common form of transitional light, other circumstances provide wonderful transitional opportunities. Just before or just after a thunderstorm when the overcast is breaking apart or just gathering are two of my favorite transitional situations. Some the most dramatic light is found where there are contrast of dark and light. Dark and ominous skies offer great contrast of grays, blacks, and whites as they mix in the atmosphere.

Fog is probably my favorite transitional light. I am always keeping tabs on the weather. Here in Kentucky we have a lot of fog...and many times the first day or so after a rain the fog will develop in the low areas and across the fields early of a morning and sometimes right at dusk.

Transitional light does not have to solely be associated with the outdoors. Reflected light bouncing off or through something is a type of transitional light as it is changed from direct light into indirect light. Some of the best moody light is that mysterious reflected light illuminating a person's face against a dark background...or filtered light coming through and opaque object like glass or thin material.

Shooting the transitions will provide potentially wonderful quality light. It's just a matter of anticipating ahead of time the conditions that might develop...and then being there. Use transitional light to your advantage and you will begin to see a transition of your images from ordinary...to extraordinary.

Keith