Sometimes I am amazed at the technology of photography today. Back in the day when I first started using a 35mm SLR camera, the technology was rather old school with just a hint of what was to come being suggested. I have to admit though, back in the day was a great learning experience and I owe a great deal to being forced to learning how to think thru the photographic process to those days.

My first experiences with using an electronic flash unit were at best rudimentary attempts of filling in light. I knew nothing about how to use a flash unit except to attach it to my camera and point it toward my subject. At best I would bounce it off a ceiling and feel like I was doing something real creative in the process. Fact is, I had no clue what I was doing and that clueless understanding followed me right up to and well into my digital transformation.

Fast forward a few years and today I use electronic flash (speed lights) units all the time and rely on them to help me create some wonderfully lit compositions. The technology today when it comes to flash units is superb. You can control the power output of multiple flash units from your camera or from the transmitter attached to your camera. Built in Through The Lens (TTL) systems in today's cameras and flash units can take a great deal of the guess work out of effectively using your flash. Of course, shooting manually opens up all kinds of creative options.

The trick then boils down to two things: Understanding how your camera interacts with a flash, and then understanding how to apply your flash unit(s) to your composition. We will in this post concentrate on the second concept. For more information on how your camera interacts with a flash you can visit a previous post: Combining Flash with Natural Light: The Mystery Unraveled https://beyondthecampfirebykeith.blogspot.com/2017/04/combining-flash-with-natural-light.html

on this blog site. Just do a blog search to find it.

We are going to break down a few photographs and explain how the flash unit was used to light the scene. The first thing to remember about using a flash unit is this: If your image looks like a flash was used, then your probably did not do your job correctly. Artificial lighting requires that it looks like it is suppose to be there. This applies to both your main source of light and any kind of secondary fill light you might use. With a few exceptions, the only time light should be noticed is if you remove it. The exceptions being if you are trying to create a specific spotlight effect or a harsh light effect.

Probably the least effective creative way to use a flash unit is to attach it to your camera and point it straight at your subject. This will almost always create a spot light effect and is a dead give away you used a flash. Sometimes you can get away with this when the light is used solely as a subtle fill light. Most of the time, flash units should be used off camera. We're not going to get into the technical how-to explanation because there are several posts on this blog that cover the how and why of doing such a thing. However we are going to look at some simple techniques of how to use an off camera flash and make it look like you were using natural light.

Why not just use natural light? Well, you can, but you cannot effectively control natural light and sometimes the quality of light just isn't there. You can with some easy to employ techniques make your speed lights look like natural light. Let's break down the photo above of the young lady. This was taken indoors on a dark and overcast day. The natural light was very flat and carried a very cool temperature. Because we were shooting indoors in a rather dark room, I needed to add some light, but not just any ordinary flash lighting would work. I needed to control several aspects of the light; the softness or tone of it, it's intensity, and the direction .

There was a large window that provided some light, but it again was very cool and flat and did not provide enough illumination to do the job effectively. To over come this, I attached an ordinary bed sheet to the outside of the window, completely covering the window. I also placed a single speedlight on a stand outside the window powered to full power shooting through the sheet into the room. The flash was about 3 feet from the window and about 7 feet or so from my subject. My exposure was manually set. I set my shutter speed (125/sec) so the ambient light in the room would just barely register, and set my aperture (f/5.6) to capture the light from the flash. ISO was 200. The bed sheet served two purposes. First is softened the light and second it turned the relatively small light source into a large light source that wrapped around my subject.

The finished photograph was exactly what I was trying to capture. A warm, soft light, that gently caressed my subject. Although it was artificial light, it appears to be natural. Using natural light from the window would have been too cool in temperature and much to direct.

This second photo above was made using the exact same setup with a slight tweak of the exposure to capture additional ambient light. Using simple tools like bed sheets is an effective method to create soft wrap around light.

The next photo was taken outdoors in a shaded environment. A single light was used and was attached to a 20x30 softbox. The exposure was set to slightly overexpose the image to allow for a high key capture...in this case the specifics were f/8.0 1/80th second ISO 200. There was quite a bit of ambient light floating around and the softbox light was moved in fairly close, probably about 2 feet way, to provide a full encompassing and overlapping fill light source. The idea here was to not create an ordinary exposure, but an exposure that would allow in post processing the ability to push the exposure out just enough to create a soft yet high key look. I wanted to keep the shadows to a minimum in this image and by moving the light close in I was able to provide just enough shadowing to enhance facial features, yet keep it subtle.

The next photo was taken using two flash units. The main light was again attached to a 20x30 softbox set about 4 feet from the model and a second light was placed on a stand set about 10 feet or so behind the model. The day was very overcast with a gray soft light diffusing through the myriad of trees in the background. The idea then was to blend both the speed lights and the ambient light into a pleasing combination. This ambient light was important to use in conjunction with the speed lights and the base exposure was set to create a subdued background. The speed lights then were used to illuminate the model and separate her from the darker background by introducing a lighting element that appeared to be coming from a natural source. The softbox generated a subtle wrapped light creating just enough shadowing to bring out her features. A straight on flash coming from the camera would have generated a less pleasing and unnatural spotlight effect.

This last image was made using two lights similar to the previous setup. The main front light was a single speed light attached to a 20x30 softbox and the second light was a single speedlight on a stand placed a few feet behind the bride. The idea here was to set an exposure that would capture the setting background and use the lights to fill in the subject. The back lighting was supplied by the second light and provided a subtle yet effect halo around the bride. This halo served to separate her from the background just enough so it appeared natural. Again, the front lighting had to appear natural. To accomplish this the 20x30 softbox diffused the light enough to soften it and was placed about 4 feet in front and to one side. This angled setting created some shadow effects but shadows are good as they bring out the features of your subject. If I had used a single light attached to the camera the effect would have been too harsh and too direct. The lighting looks like it is suppose to be there.

The idea then is for the lighting to enhance your subject but not to look like you were lighting it. That is the subtle nature of using speed lights. How much is enough and how much is too much.? Those are questions answered through experience. A subtle touch of light is often all that is required to create a wonderfully lit composition.

ESTABLISHED 2010 - Beyond The Campfire was created to encourage readers to explore the great outdoors and to observe it close up. Get out and take a hike, go fishing or canoeing, or simply stretch out on a blanket under a summer sky...and take your camera along. We'll talk about combining outdoor activities with photography. We'll look at everything from improving your understanding of the basics of photography to more advanced techniques including things like how to see photographically and capturing the light. We'll explore the night sky, location shoots, using off camera speedlights along with nature and landscape. Grab your camera...strap on your hiking boots...and join me. I think you will enjoy the adventure.

Tuesday, August 7, 2018

Thursday, August 2, 2018

Other Values - The Fine Pleasantries of Being a Photographer

It was a typical early summer day on Oklahoma's Tallgrass Prairie , hot and windy, and as the day tumbled toward its last few moments of daylight, I felt a bit relieved when the heat of the day began to dissipate behind the few clouds that hovered above the horizon. The high knoll upon which I stood offered a 360 degree view of the surrounding landscape, magnificent, awe inspiring, simply beautiful. Shadows began to grow longer and filled the gaps between the undulations of the land. Somewhere off to the south a family of coyotes began to howl and their movement caught my eye as they set out in pursuit of dinner. I watched them as best as I could until they were gone. Just knowing they were there added to the natural flavor of the moment.

My camera attached to my tripod stood ready to capture the last vestiges of the day anticipating one of those legendary prairie sunsets. For some reason, I sat silent and made no attempt to capture a photograph. The moment lived of itself and presented to me an image in such a way that a single photograph could never capture the essence of what was there. There were other values at play, values which are only experienced emotionally, pleasures for sure of being a photographer.

As a photographer I have been fortunate to have experienced a great many such moments. They were moments captured by the imagination that otherwise would have been lost. As much as I relish capturing amazing moments of light, I relish as much the experiences associated with having been there to do so. There are other values to being a photographer which are difficult to convey and can most easily be appreciated by having experienced them yourself. Being a photographer of light places you next to moments such as those if you are willing to be there.

I once had a friend who I took fishing with me. He was a nice enough sort of fellow, but as our fishing trip turned into one of those 'nothing was biting' kind of days, his complaining about the day being a big waste of time began to dominate his conversation. By the time we pulled out, I was certain I would never again take this person fishing. He completely missed what it was all about. He focused on catching fish as the measure of our day. I focused on just being out and enjoying the day. When the fishing portion of our day went bust, his day was ruined, but, other than having to listen to his griping about it, my day was just fine. Photography is the same way. There are days where things simply do not work, but the point is to enjoy just being there to allow the day to present itself to you in whatever mood it happens to be in.

Because of photography I have witnessed amazing sunsets and sunrises. I have felt the wind and rain across my back. I have been caught in violent storms and other amazing moments of nature. I have seen the delicate forms of creation, and followed the life cycle of a nest of Robins. I have known the boldness of fall colors and the intense grip of a winter blizzard. I have been thirsty, cold, tired, wet, and sunburned, yet I have also captured amazing moments of natures light. I have missed sleep, and stayed out until the early hours of the morning to capture a night sky so filled with wonder it defies our sense of what is out there.

I have canoed, hiked, and driven countless miles to hopefully capture that one photograph I knew might be there, and then did it again and again, until the photo I wanted finally appeared. I have captured the subtle beauty of the human form and the aggressive forms of wild nature. The exhilaration of having been there to experience all of these kinds of moments far outpaces the discomfort for having done so. Rewards for being a photographer are not always granted based on outcome. They are more often given for having made the effort. When the moment pays off with a spectacular image...well, the reward is self fulfilling.

My camera attached to my tripod stood ready to capture the last vestiges of the day anticipating one of those legendary prairie sunsets. For some reason, I sat silent and made no attempt to capture a photograph. The moment lived of itself and presented to me an image in such a way that a single photograph could never capture the essence of what was there. There were other values at play, values which are only experienced emotionally, pleasures for sure of being a photographer.

As a photographer I have been fortunate to have experienced a great many such moments. They were moments captured by the imagination that otherwise would have been lost. As much as I relish capturing amazing moments of light, I relish as much the experiences associated with having been there to do so. There are other values to being a photographer which are difficult to convey and can most easily be appreciated by having experienced them yourself. Being a photographer of light places you next to moments such as those if you are willing to be there.

I once had a friend who I took fishing with me. He was a nice enough sort of fellow, but as our fishing trip turned into one of those 'nothing was biting' kind of days, his complaining about the day being a big waste of time began to dominate his conversation. By the time we pulled out, I was certain I would never again take this person fishing. He completely missed what it was all about. He focused on catching fish as the measure of our day. I focused on just being out and enjoying the day. When the fishing portion of our day went bust, his day was ruined, but, other than having to listen to his griping about it, my day was just fine. Photography is the same way. There are days where things simply do not work, but the point is to enjoy just being there to allow the day to present itself to you in whatever mood it happens to be in.

Because of photography I have witnessed amazing sunsets and sunrises. I have felt the wind and rain across my back. I have been caught in violent storms and other amazing moments of nature. I have seen the delicate forms of creation, and followed the life cycle of a nest of Robins. I have known the boldness of fall colors and the intense grip of a winter blizzard. I have been thirsty, cold, tired, wet, and sunburned, yet I have also captured amazing moments of natures light. I have missed sleep, and stayed out until the early hours of the morning to capture a night sky so filled with wonder it defies our sense of what is out there.

I have canoed, hiked, and driven countless miles to hopefully capture that one photograph I knew might be there, and then did it again and again, until the photo I wanted finally appeared. I have captured the subtle beauty of the human form and the aggressive forms of wild nature. The exhilaration of having been there to experience all of these kinds of moments far outpaces the discomfort for having done so. Rewards for being a photographer are not always granted based on outcome. They are more often given for having made the effort. When the moment pays off with a spectacular image...well, the reward is self fulfilling.

Saturday, July 28, 2018

Breaking Into Astrophotography Part 3 - Tracking the Stars

In our previous post we looked at how to photograph the Milky Way with ordinary DSLR equipment using a 30 second exposure and a wide angle lens. For most night sky photography this process works well and can offer a tremendous amount of satisfaction in capturing the wonders of the night sky. Sometimes though, we may want to increase our exposure times to accumulate more light, or we may want to use a longer, more powerful lens to look at deep sky objects, or to simply gather more digital information from the Milky Way in order to bring out more details. To do so requires that you be able to track your camera at the same rate as the apparent motion of the stars across the sky. We do this by employing a Star Tracker. As the final of our 3 part series of Breaking into Astrophotography, let's take a look at how we do this.

What You Need To Know: Standing outside in a field looking up at a star filled night sky, the stars may appear to be motionless. To our unaided eyes, they do indeed appear that way, but the earth is spinning like a top and because of that, the stars do move across our field of view. When photographing them with a wide angle, you can take relatively long exposures and still have the stars appear as pin points of light. That is because they are so small relative to the field of view. However if you allow the exposure to continue past 30 seconds or so, those stars will begin to show a trailing tail or an elongated streak.

The longer you go, the more pronounced the streaks. In order to capture longer duration exposures, a star tracking devise is necessary. Star Trackers are relatively simple devises that compensate for the rotation of the earth and keep the camera pointing at the same spot in the sky regardless of earth's rotation. There are a variety of types both commercial and homemade.

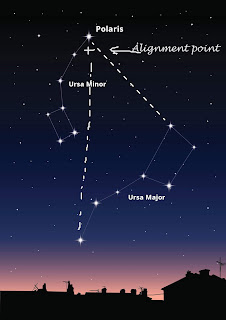

Facing north, about 40 degrees or so above the horizon in the northern hemisphere sits Polaris, the Pole Star. Polaris appears to be stationary while all the other stars rotate around it. That is because the earths north pole is almost aligned exactly with Polaris...it's actually a little bit off, but more on that later. Polaris is actually the last star in the handle of the constellation known as the Little Dipper, or by some as the Little Bear, or Ursa Minor. It is not a particularly bright star, but easily sighted with a little help.

Not far from the Little Dipper lies it's larger cousin called The Big Dipper (Big Bear or Ursa Major), perhaps the easiest to locate and best known constellation in the sky. The outer two stars of the Big Dipper's cup roughly point toward Polaris making it relatively easy to locate.

Polaris is very important when trying to photograph the night sky by using a tracking devise and we will explain that in a moment.

Star Trackers: As already stated, there are numerous commercially produced Star Trackers. Some are designed to track the sky using a telescope that allows you to attach a camera to it piggy-back style. Others are stand alone units that mount onto a sturdy tripod, and still others are simple devises call Barn Door Star Trackers that you can make yourself. All of them, however different in design, accomplish the same thing. They simply track the sky at the same rate of motion of the earths spin. We will limit our discussion to using a DIY Star Tracker known as a Barn Door Tracker.

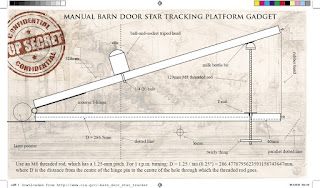

The Barn Door Tracker: As mentioned, you can opt to purchase a commercially available tracker or you can build one yourself. The most common DIY tracker is the Barn Door variety. Let's take a look at how they are built and operate. There are as many varieties of Barn Door trackers as there are people who build them, but they all operate basically the same way. Two pieces, usually wooden boards, are hinged at one end with a single screw type drive shaft, that can be hand operated or motor driven, at the other end. The basic idea of their operation is to attach the camera to a small ball head on the upper board near the hinge, and for the drive shaft to turn one full revolution per minute which, because of the screw action of the shaft, moves the upper board in a shallow arch. The arch movement mimics the movement of the sky.

There are some relatively precise measurements that must be applied to it's construction, but all of that depends on the design of the unit, and there are numerous designs available online. A basic unit will cost less than $20.00 to build. Even with some enhancements, I have less than $40.00 invested in mine.

Using The Barn Door Tracker: To use the Barn Door Tracker, it must first be attached to a sturdy Tripod of some type. I use an old equitorial telescope tripod mount from an inexpensive telescope I used to have which works great, but just about any sturdy tripod will work when the tracker is properly secured in place.

It also needs to be aligned with Polaris with some degree of accuracy. The alignment point falls approximately midway between Polaris and the Star just in front of it, known as Yildan, on the Little Dipper's handle and must be on a line that intersects Polaris and the last inside star, of the Big Dippers handle. (See Photo) This offset alignment is known as the North Celestial Pole or NCP. It represents the actual point the north pole points to. Polaris actually rotates around this point as the earth spins. There are other stars near Polaris that can be used to refine the alignment, but for wide angle photographs of limited time say up to 2 minutes or so, this alignment configuration will work very well. Certain times of the year the Big Dippers handle is not easily seen as it sits quite low in the sky, so you can use the last star in the Little Dippers cup as a reference alignment point...just make the connecting line run slightly outside of where it sits.

To make the alignment, you must adjust the Tripod in such a way so the Hinge is on the left and is pointing at the indicated alignment point. Some builders use a simple soda straw that is attached to the hinge to aide in the alignment, some use a green laser pointer. On my tracker I attached an old 4X rifle scope to the hinge mounting with a simple bracket. The small scope helps with finding Polaris and the cross hair X helps with precisely pointing it to the correct alignment point. Please note, the relative Alignment point will change through the season as the Big and Little Dipper's rotate across the sky. Sometimes it will be located below Polaris, later in the year it will be above it. It just depends on the seasonal orientation of the Little Dipper.

To operate a basic tracker design, you can simply attach an arm on the drive shaft and rotate it by gently turning it with your finger...Every 15 seconds you simply rotate it 1/4 turn. Over the course of one minute, you will have turned the shaft 1/4 turn 4 times and it will make the required full 360 degree turn. You can make accurate exposures up to several minutes long with this method if you are careful. This works well if you are simply shooting the stars with a relatively wide angle lens. However, should you use a longer focal length lens, a small 1 rpm battery driven electric motor will operate the tracking rotation much more smoothly allowing for more accurate tracking. The motor in effect replaces your turning finger and helps to eliminate possible vibrations caused by that kind of manual rotation. The motor provides a continuous motion, while the manually turned method is stop and go.

Over the course of a couple of years I modified my tracker to use such a motor and also attached a digital voltage regulator that allowed me to precisely control the voltage going to the motor. This helps to insure the tracker is rotating at exactly 1 rpm.

Why Should I Bother With a Tracker: A tracker allows you to make longer exposures which gathers in more light thus creating a more detailed image. It is also necessary if you want to capture deep sky objects like the Orion Nebula or Andromeda. Without a tracker, doing so becomes much more problematic. I have used upwards to a 500 mm lens. It is about the maximum it can support simply because of the weight, but it does work well. Remember too, you do not always need a lot of magnifying power, bu you do need resolving power and that is where a good quality lens comes in. Also, remember, the larger the lens, the more critical the alignment becomes and the more critical vibrations become. A 500 mm lens will magnify even the slightest movement of the tripod or tracking devise. The key points are to have the devise properly and accurately aligned and for it to be sturdy.

There are other ways to capture deep sky objects most of them require you to take a series, at least 100 to 300 shots, of short duration exposures and use a specialize software to 'Stack' them into a finished image. These stacked images include images used to cancel out noise, but the results can be spectacular. However, using Stacking software requires a lot of computer power and they are not always user friendly.

Summing Up: Every season I look forward to once again hearing the buzz of the tracking motor and to watch the tracker doing its thing. Most of all, I look forward to seeing and sharing the results.

Photographing the night sky is a learned skill that virtually any photographer can do with a little practice. I hope this short 3 part series has peaked your interest in this fascinating form of photography. I promise you, once you have tried it, your interest in Astronomy and 'What's Out There' will surely increase.

|

| Dark Horse Detail - 103 Sec @ f/3.5 35mm ISO 800 |

What You Need To Know: Standing outside in a field looking up at a star filled night sky, the stars may appear to be motionless. To our unaided eyes, they do indeed appear that way, but the earth is spinning like a top and because of that, the stars do move across our field of view. When photographing them with a wide angle, you can take relatively long exposures and still have the stars appear as pin points of light. That is because they are so small relative to the field of view. However if you allow the exposure to continue past 30 seconds or so, those stars will begin to show a trailing tail or an elongated streak.

|

| Untracked stars scene - 40 Sec f/4.5 ISO 800 using a 105mm lens Notice the star trails |

The longer you go, the more pronounced the streaks. In order to capture longer duration exposures, a star tracking devise is necessary. Star Trackers are relatively simple devises that compensate for the rotation of the earth and keep the camera pointing at the same spot in the sky regardless of earth's rotation. There are a variety of types both commercial and homemade.

|

| Tracked 60 sec f/4.5 ISO 800 105mm No star trails |

Not far from the Little Dipper lies it's larger cousin called The Big Dipper (Big Bear or Ursa Major), perhaps the easiest to locate and best known constellation in the sky. The outer two stars of the Big Dipper's cup roughly point toward Polaris making it relatively easy to locate.

Polaris is very important when trying to photograph the night sky by using a tracking devise and we will explain that in a moment.

Star Trackers: As already stated, there are numerous commercially produced Star Trackers. Some are designed to track the sky using a telescope that allows you to attach a camera to it piggy-back style. Others are stand alone units that mount onto a sturdy tripod, and still others are simple devises call Barn Door Star Trackers that you can make yourself. All of them, however different in design, accomplish the same thing. They simply track the sky at the same rate of motion of the earths spin. We will limit our discussion to using a DIY Star Tracker known as a Barn Door Tracker.

The Barn Door Tracker: As mentioned, you can opt to purchase a commercially available tracker or you can build one yourself. The most common DIY tracker is the Barn Door variety. Let's take a look at how they are built and operate. There are as many varieties of Barn Door trackers as there are people who build them, but they all operate basically the same way. Two pieces, usually wooden boards, are hinged at one end with a single screw type drive shaft, that can be hand operated or motor driven, at the other end. The basic idea of their operation is to attach the camera to a small ball head on the upper board near the hinge, and for the drive shaft to turn one full revolution per minute which, because of the screw action of the shaft, moves the upper board in a shallow arch. The arch movement mimics the movement of the sky.

|

| Internet Photos |

There are some relatively precise measurements that must be applied to it's construction, but all of that depends on the design of the unit, and there are numerous designs available online. A basic unit will cost less than $20.00 to build. Even with some enhancements, I have less than $40.00 invested in mine.

Using The Barn Door Tracker: To use the Barn Door Tracker, it must first be attached to a sturdy Tripod of some type. I use an old equitorial telescope tripod mount from an inexpensive telescope I used to have which works great, but just about any sturdy tripod will work when the tracker is properly secured in place.

It also needs to be aligned with Polaris with some degree of accuracy. The alignment point falls approximately midway between Polaris and the Star just in front of it, known as Yildan, on the Little Dipper's handle and must be on a line that intersects Polaris and the last inside star, of the Big Dippers handle. (See Photo) This offset alignment is known as the North Celestial Pole or NCP. It represents the actual point the north pole points to. Polaris actually rotates around this point as the earth spins. There are other stars near Polaris that can be used to refine the alignment, but for wide angle photographs of limited time say up to 2 minutes or so, this alignment configuration will work very well. Certain times of the year the Big Dippers handle is not easily seen as it sits quite low in the sky, so you can use the last star in the Little Dippers cup as a reference alignment point...just make the connecting line run slightly outside of where it sits.

To make the alignment, you must adjust the Tripod in such a way so the Hinge is on the left and is pointing at the indicated alignment point. Some builders use a simple soda straw that is attached to the hinge to aide in the alignment, some use a green laser pointer. On my tracker I attached an old 4X rifle scope to the hinge mounting with a simple bracket. The small scope helps with finding Polaris and the cross hair X helps with precisely pointing it to the correct alignment point. Please note, the relative Alignment point will change through the season as the Big and Little Dipper's rotate across the sky. Sometimes it will be located below Polaris, later in the year it will be above it. It just depends on the seasonal orientation of the Little Dipper.

To operate a basic tracker design, you can simply attach an arm on the drive shaft and rotate it by gently turning it with your finger...Every 15 seconds you simply rotate it 1/4 turn. Over the course of one minute, you will have turned the shaft 1/4 turn 4 times and it will make the required full 360 degree turn. You can make accurate exposures up to several minutes long with this method if you are careful. This works well if you are simply shooting the stars with a relatively wide angle lens. However, should you use a longer focal length lens, a small 1 rpm battery driven electric motor will operate the tracking rotation much more smoothly allowing for more accurate tracking. The motor in effect replaces your turning finger and helps to eliminate possible vibrations caused by that kind of manual rotation. The motor provides a continuous motion, while the manually turned method is stop and go.

Over the course of a couple of years I modified my tracker to use such a motor and also attached a digital voltage regulator that allowed me to precisely control the voltage going to the motor. This helps to insure the tracker is rotating at exactly 1 rpm.

Why Should I Bother With a Tracker: A tracker allows you to make longer exposures which gathers in more light thus creating a more detailed image. It is also necessary if you want to capture deep sky objects like the Orion Nebula or Andromeda. Without a tracker, doing so becomes much more problematic. I have used upwards to a 500 mm lens. It is about the maximum it can support simply because of the weight, but it does work well. Remember too, you do not always need a lot of magnifying power, bu you do need resolving power and that is where a good quality lens comes in. Also, remember, the larger the lens, the more critical the alignment becomes and the more critical vibrations become. A 500 mm lens will magnify even the slightest movement of the tripod or tracking devise. The key points are to have the devise properly and accurately aligned and for it to be sturdy.

There are other ways to capture deep sky objects most of them require you to take a series, at least 100 to 300 shots, of short duration exposures and use a specialize software to 'Stack' them into a finished image. These stacked images include images used to cancel out noise, but the results can be spectacular. However, using Stacking software requires a lot of computer power and they are not always user friendly.

|

| Andromeda Galaxy Tracked exposure |

Photographing the night sky is a learned skill that virtually any photographer can do with a little practice. I hope this short 3 part series has peaked your interest in this fascinating form of photography. I promise you, once you have tried it, your interest in Astronomy and 'What's Out There' will surely increase.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)